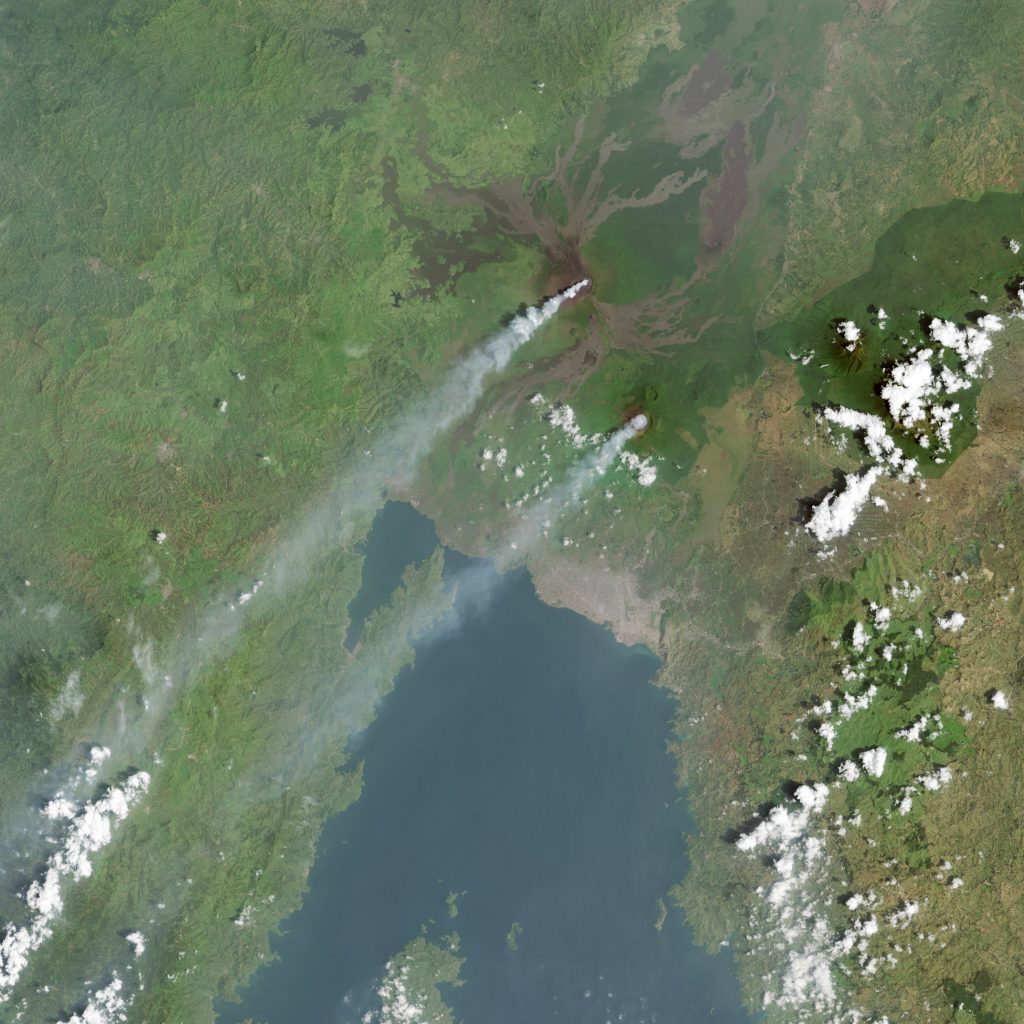

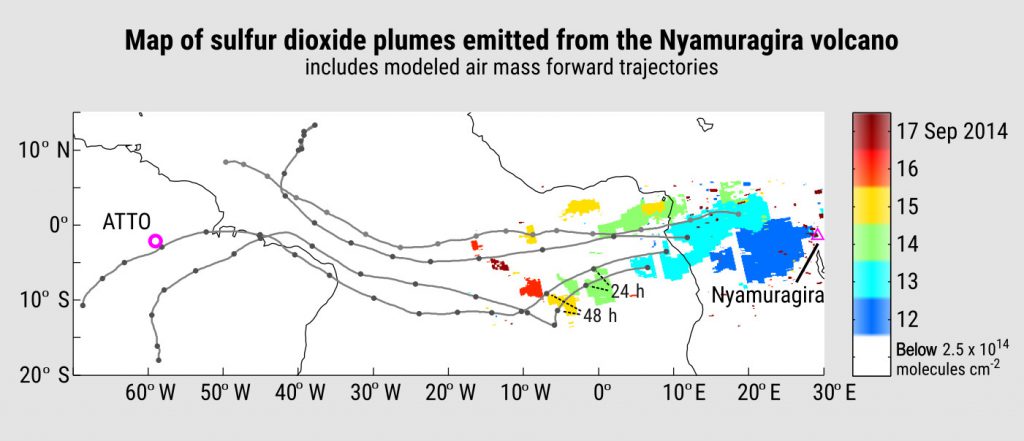

The long-range transport of particles, such as sulfate, across the Atlantic to the Amazon rainforest can help to better understand atmospheric cycling. A good opportunity for that arose in 2014. Some of the most active volcanoes worldwide, the Nyamuragira and Mount Nyiragongo volcanoes in Congo in Central Africa, erupted violently.

During this eruption, they emitted a lot of sulfur dioxide (SO2) into the atmosphere. This gas that is later converted to sulfate particles by oxidation. Usually, these particles are diluted in the atmosphere as they mix with other particles. It thus becomes difficult to distinguish them far away from their source. However, the emissions of 2014 were so strong that the sulfate particles originating from the volcanic gas were observed over the Amazon rainforest by ground-based instruments at our ATTO site (specifically at the 80 m tall triangular mast) and by aircraft measurements (during the ACRIDICON-CHUVA campaign). This observation is now being used by ATTO scientists as a case study to understand how gas and particle emissions from Africa are transported over the Atlantic Ocean and reach the Amazon Basin.

For scale, the volcanoes in Congo are almost 10,000 km away from ATTO, and it took the particles around 2 weeks to bridge that distance!

The full study was just published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (ACP) Issue 18 by first author Jorge Saturno. It is available Open Access and thus freely available for everyone.

Similar articles

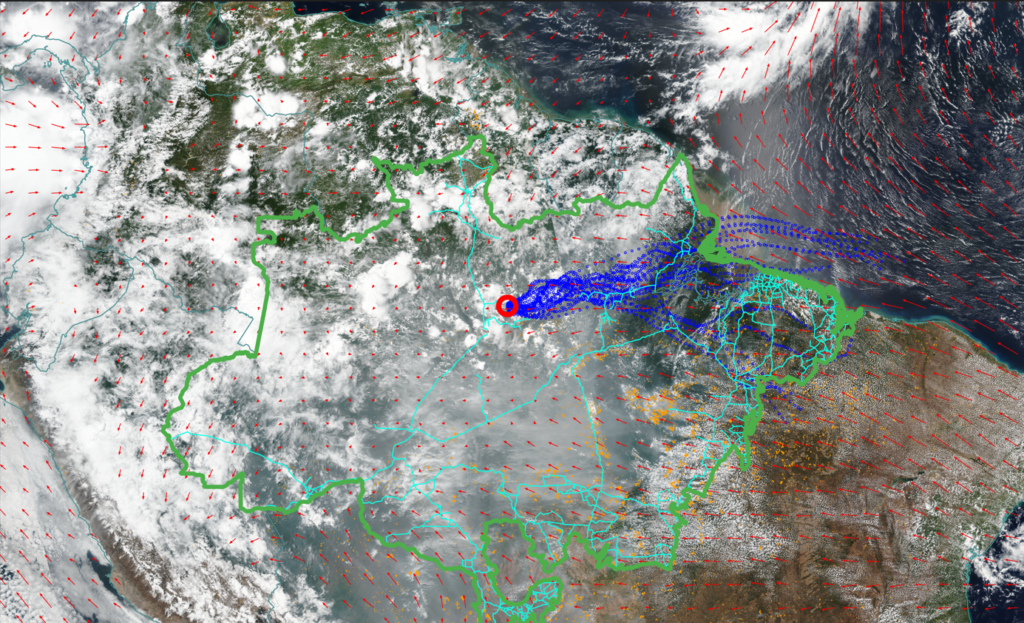

When forests burn those fires produce a lot of smoke. And that smoke usually contains soot, also called “black carbon”. Black carbon particles are aerosols that absorb radiation and as such can warm the Earth’s atmosphere and climate. But we still have much to learn about aerosols, their properties, and distribution in the atmosphere. One of those things is the question of how black carbon emitted from biomass burning in Africa (i.e. forests, grasslands, savannas etc.) is transported across the Atlantic and into the Amazon basin, and what role it plays there. Bruna Holanda and her co-authors tackled this in their new study published in ACP.

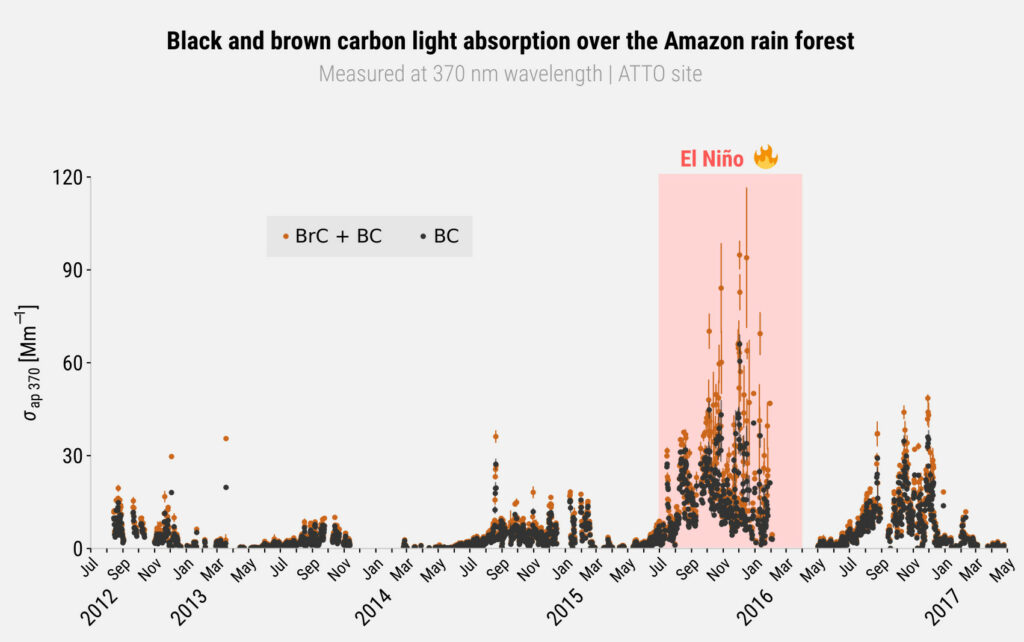

Saturno et al. analyzed the concentration of black and brown carbon in the atmosphere above the Amazon. They found that the dry season is characterized by lots of biomass burnings, which produce a lot of black and brown carbon. But they also sound significant interannual variations. The results were published in ACP.

More soot particles enter the central Amazon rainforest from brush fires in Africa than from regional fires at certain times.

Bioaerosols influence the dynamics of the biosphere underneath. In a new study, Sylvia Mota de Oliveira and her colleagues used the ATTO site to collect air samples at 300 m above the forest. Then, they used DNA sequencing to analyze the biological components that were present and figure out what species of plant or fungi they belong to. One of the most striking new insights is the stark contrast between the species composition in the near-pristine Amazonian atmosphere compared to urban areas.

Ramsay et al. measured inorganic trace gases such as ammonia and nitric acid and aerosols in the dry season at ATTO. They are to serve as baseline values for their concentration and fluxes in the atmosphere and are a first step in deciphering exchange processes of inorganic trace gases between the Amazon rainforest and the atmosphere.

Soot and other aerosols from biomass burning can influence regional and global weather and climate. Lixia Liu and her colleagues studied how this affects the Amazon Basin during the dry season. While there are many different interactions between biomass burning aerosols and climate, they found that they overall lead to fewer and weaker rain events in the Amazon rainforest.

When forests burn those fires produce a lot of smoke. And that smoke usually contains soot, also called “black carbon”. Black carbon particles are aerosols that absorb radiation and as such can warm the Earth’s atmosphere and climate. But we still have much to learn about aerosols, their properties, and distribution in the atmosphere. One of those things is the question of how black carbon emitted from biomass burning in Africa (i.e. forests, grasslands, savannas etc.) is transported across the Atlantic and into the Amazon basin, and what role it plays there. Bruna Holanda and her co-authors tackled this in their new study published in ACP.

Saturno et al. analyzed the concentration of black and brown carbon in the atmosphere above the Amazon. They found that the dry season is characterized by lots of biomass burnings, which produce a lot of black and brown carbon. But they also sound significant interannual variations. The results were published in ACP.

More soot particles enter the central Amazon rainforest from brush fires in Africa than from regional fires at certain times.

Bioaerosols influence the dynamics of the biosphere underneath. In a new study, Sylvia Mota de Oliveira and her colleagues used the ATTO site to collect air samples at 300 m above the forest. Then, they used DNA sequencing to analyze the biological components that were present and figure out what species of plant or fungi they belong to. One of the most striking new insights is the stark contrast between the species composition in the near-pristine Amazonian atmosphere compared to urban areas.

Ramsay et al. measured inorganic trace gases such as ammonia and nitric acid and aerosols in the dry season at ATTO. They are to serve as baseline values for their concentration and fluxes in the atmosphere and are a first step in deciphering exchange processes of inorganic trace gases between the Amazon rainforest and the atmosphere.

Soot and other aerosols from biomass burning can influence regional and global weather and climate. Lixia Liu and her colleagues studied how this affects the Amazon Basin during the dry season. While there are many different interactions between biomass burning aerosols and climate, they found that they overall lead to fewer and weaker rain events in the Amazon rainforest.

When forests burn those fires produce a lot of smoke. And that smoke usually contains soot, also called “black carbon”. Black carbon particles are aerosols that absorb radiation and as such can warm the Earth’s atmosphere and climate. But we still have much to learn about aerosols, their properties, and distribution in the atmosphere. One of those things is the question of how black carbon emitted from biomass burning in Africa (i.e. forests, grasslands, savannas etc.) is transported across the Atlantic and into the Amazon basin, and what role it plays there. Bruna Holanda and her co-authors tackled this in their new study published in ACP.

Saturno et al. analyzed the concentration of black and brown carbon in the atmosphere above the Amazon. They found that the dry season is characterized by lots of biomass burnings, which produce a lot of black and brown carbon. But they also sound significant interannual variations. The results were published in ACP.