Scientists from our Aerosol group published a new “Long-term study on coarse mode aerosols in the Amazon rainforest with the frequent intrusion of Saharan dust plumes”.

They analyzed the coarse fraction of aerosols (those that are at least 1 micrometer in diameter) every 5 minutes for over 3 years and were surprised to find that over this period the size and abundance of these “large” aerosol particles remained fairly constant. In contrast, the smaller aerosols are heavily influenced by the seasonal occurrence of smoke from fires. This coarse fraction, however, is mainly comprised of aerosols derived from the rainforest itself (such as pollen). That pattern only changes during the wet season (December through April), when Saharan dust, sea salt particles from the Atlantic and smoke from fires in Africa episodically make their way to the Amazon. Especially in February and March, pulses of African aerosols become so frequent they are the norm rather than the exception. Our scientists then used these data to estimate how much dust is deposited in the ATTO region each year: 5-10 kg per hectare, or 0.5-1 g per square meter.

You can read the full study by lead author Daniel Moran-Zuloaga in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Issue 18. It is published Open Access and thus freely available online. The data set is also available for further analysis (see publication for details)!

Similar articles

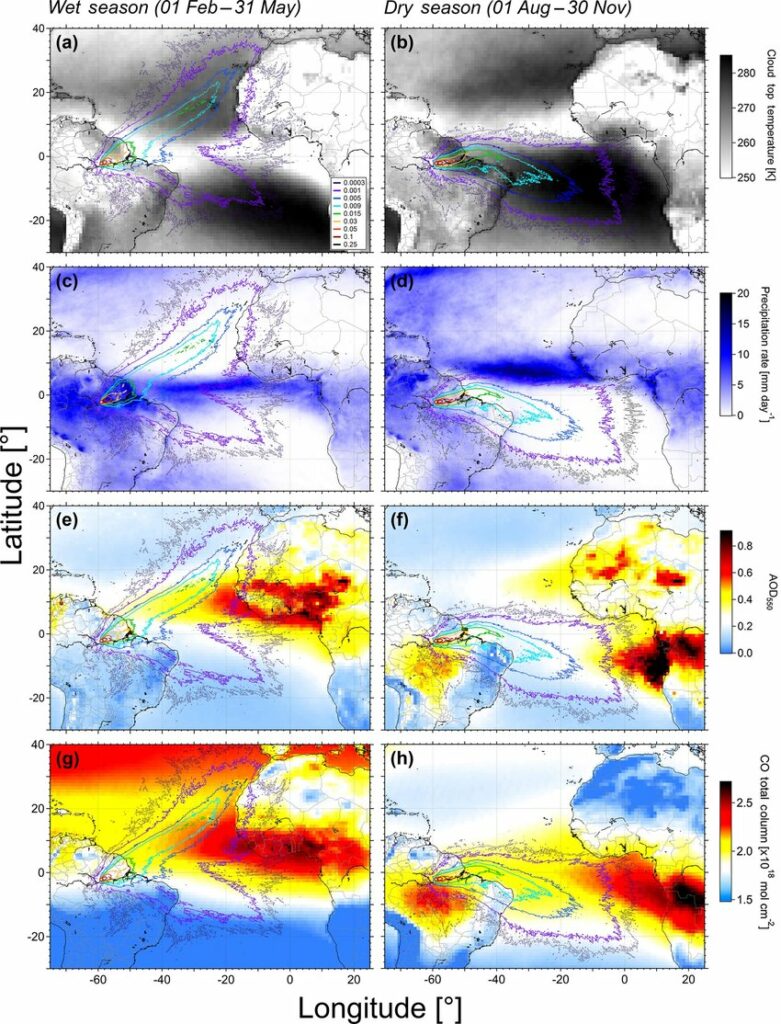

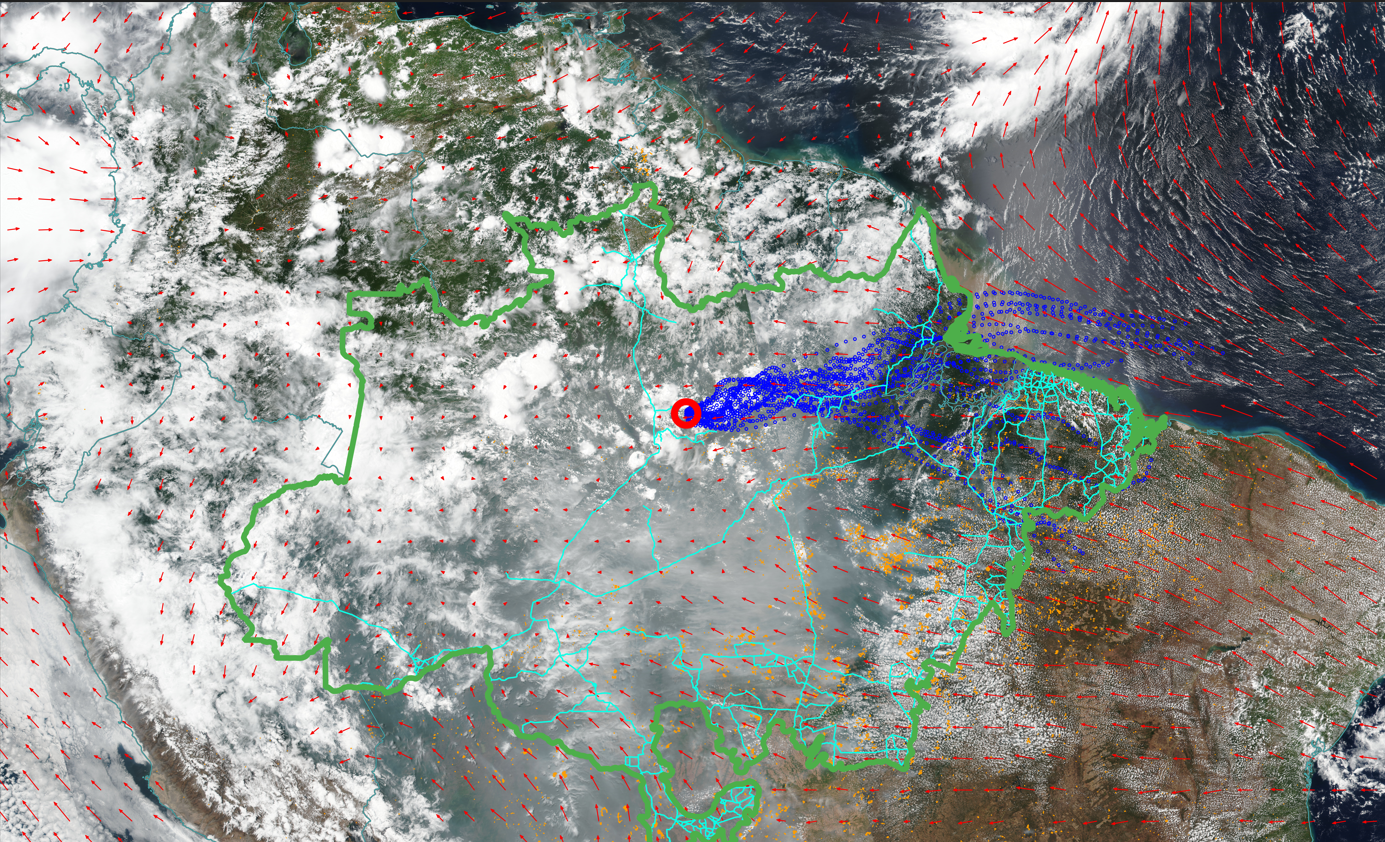

When forests burn those fires produce a lot of smoke. And that smoke usually contains soot, also called “black carbon”. Black carbon particles are aerosols that absorb radiation and as such can warm the Earth’s atmosphere and climate. But we still have much to learn about aerosols, their properties, and distribution in the atmosphere. One of those things is the question of how black carbon emitted from biomass burning in Africa (i.e. forests, grasslands, savannas etc.) is transported across the Atlantic and into the Amazon basin, and what role it plays there. Bruna Holanda and her co-authors tackled this in their new study published in ACP.

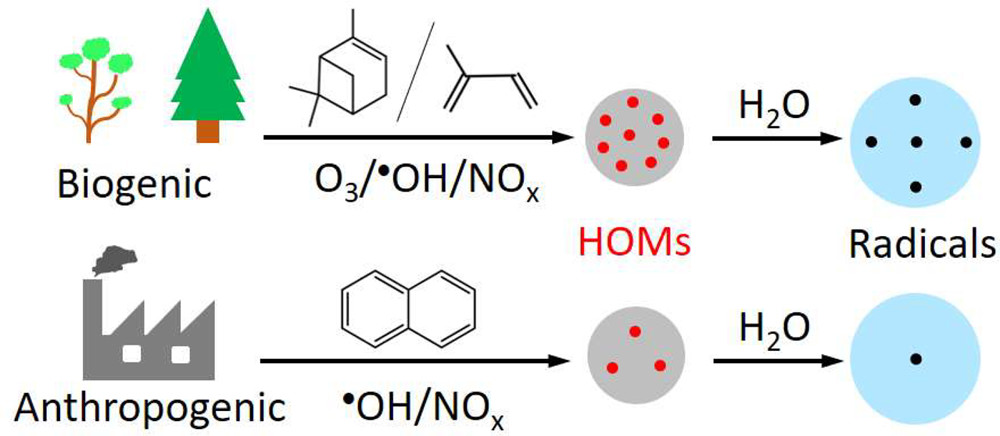

In a new study, Dr. Haijie Tong and co-authors studied a subset of PM2.5, the so-called highly oxygenated molecules (HOMs) and its relationship with radical yield and aerosol oxidative potential. They analyzed fine particulate matter in the air in multiple locations. This including the highly polluted megacity Bejing and in the pristine rainforest at ATTO. They wanted to get insights into the chemical characteristic and evolutions of these HOM particles. In particular, they wanted to find out more about the potential of HOMs to form free radicals. These are highly reactive species with unpaired electrons.

Atmospheric aerosol particles are essential for the formation of clouds and precipitation, thereby influencing the Earth’s energy budget, water cycle, and climate. However, the origin of aerosol particles in pristine air over the Amazon rainforest during the wet season is poorly understood. A new study reveals that rainfall regularly induces bursts of newly formed nanoparticles in the air above the forest canopy.

More soot particles enter the central Amazon rainforest from brush fires in Africa than from regional fires at certain times.

Bioaerosols influence the dynamics of the biosphere underneath. In a new study, Sylvia Mota de Oliveira and her colleagues used the ATTO site to collect air samples at 300 m above the forest. Then, they used DNA sequencing to analyze the biological components that were present and figure out what species of plant or fungi they belong to. One of the most striking new insights is the stark contrast between the species composition in the near-pristine Amazonian atmosphere compared to urban areas.

In a new study, Marco A. Franco and his colleagues analyzed when and under what conditions aerosols grow to a size relevant for cloud formation. Such growth events are relatively rare in the Amazon rainforest and follow and pronounced diurnal and seasonal cycles. The majority take place during the daytime, and during the wet season. But the team also discovered a few remarkable exceptions.

It is long known that aerosols, directly and indirectly, affect clouds and precipitation. But very few studies have focused on the opposite: the question of how clouds modify aerosol properties. Therefore, Luiz Machado and his colleagues looked into this process at ATTO. Specifically, they studied how weather events influenced the size distribution of aerosol particles.

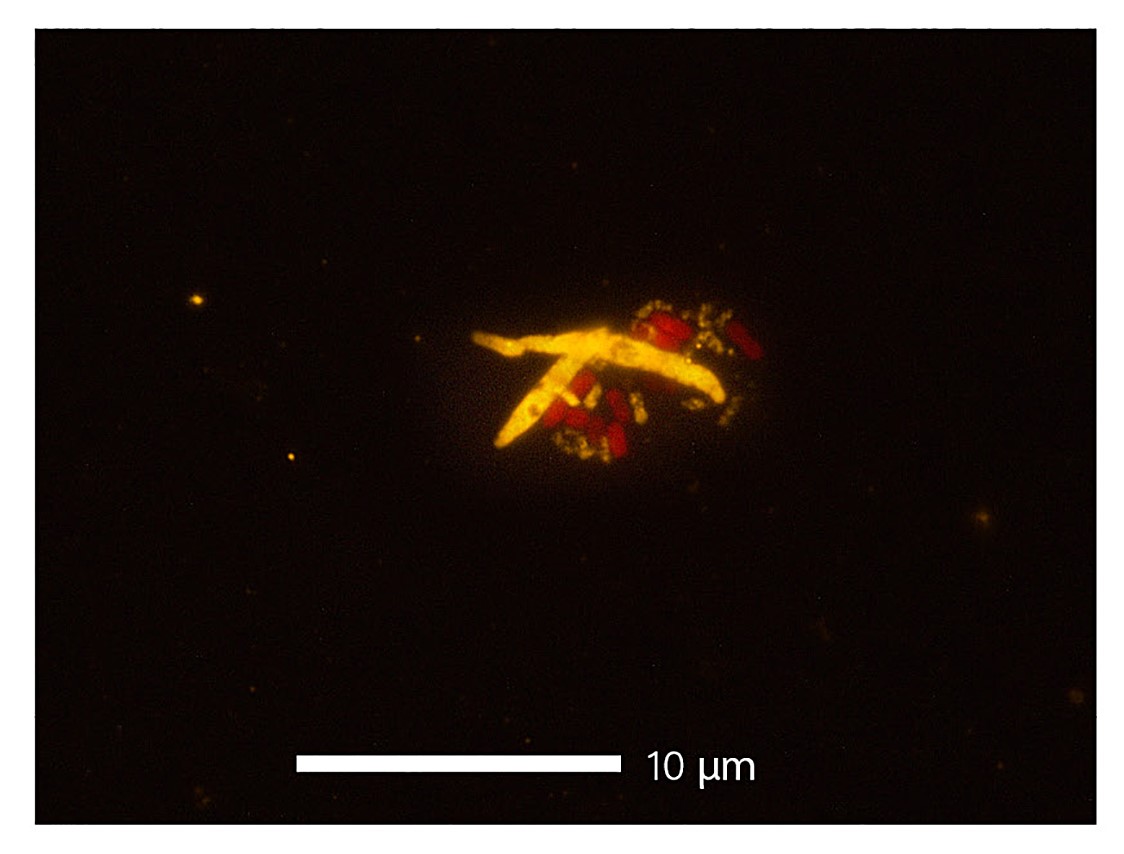

The Amazon rain forest plays a major role in global hydrological cycling. Biogenic aerosols, such as pollen, fungi, and spores likely influence the formation of clouds and precipitation. However, there are many different types of bioaerosols. The particles vary considerably in size, morphology, mixing state, as well as behavior like hygroscopicity (how much particles attract water) and metabolic activity. Therefore, it is likely that not only the amount of bioaerosols affects the hydrological cycle, but also the types of aerosols present.

Ramsay et al. measured inorganic trace gases such as ammonia and nitric acid and aerosols in the dry season at ATTO. They are to serve as baseline values for their concentration and fluxes in the atmosphere and are a first step in deciphering exchange processes of inorganic trace gases between the Amazon rainforest and the atmosphere.

Soot and other aerosols from biomass burning can influence regional and global weather and climate. Lixia Liu and her colleagues studied how this affects the Amazon Basin during the dry season. While there are many different interactions between biomass burning aerosols and climate, they found that they overall lead to fewer and weaker rain events in the Amazon rainforest.

When forests burn those fires produce a lot of smoke. And that smoke usually contains soot, also called “black carbon”. Black carbon particles are aerosols that absorb radiation and as such can warm the Earth’s atmosphere and climate. But we still have much to learn about aerosols, their properties, and distribution in the atmosphere. One of those things is the question of how black carbon emitted from biomass burning in Africa (i.e. forests, grasslands, savannas etc.) is transported across the Atlantic and into the Amazon basin, and what role it plays there. Bruna Holanda and her co-authors tackled this in their new study published in ACP.

In a new study, Dr. Haijie Tong and co-authors studied a subset of PM2.5, the so-called highly oxygenated molecules (HOMs) and its relationship with radical yield and aerosol oxidative potential. They analyzed fine particulate matter in the air in multiple locations. This including the highly polluted megacity Bejing and in the pristine rainforest at ATTO. They wanted to get insights into the chemical characteristic and evolutions of these HOM particles. In particular, they wanted to find out more about the potential of HOMs to form free radicals. These are highly reactive species with unpaired electrons.

Atmospheric aerosol particles are essential for the formation of clouds and precipitation, thereby influencing the Earth’s energy budget, water cycle, and climate. However, the origin of aerosol particles in pristine air over the Amazon rainforest during the wet season is poorly understood. A new study reveals that rainfall regularly induces bursts of newly formed nanoparticles in the air above the forest canopy.

More soot particles enter the central Amazon rainforest from brush fires in Africa than from regional fires at certain times.

Bioaerosols influence the dynamics of the biosphere underneath. In a new study, Sylvia Mota de Oliveira and her colleagues used the ATTO site to collect air samples at 300 m above the forest. Then, they used DNA sequencing to analyze the biological components that were present and figure out what species of plant or fungi they belong to. One of the most striking new insights is the stark contrast between the species composition in the near-pristine Amazonian atmosphere compared to urban areas.

In a new study, Marco A. Franco and his colleagues analyzed when and under what conditions aerosols grow to a size relevant for cloud formation. Such growth events are relatively rare in the Amazon rainforest and follow and pronounced diurnal and seasonal cycles. The majority take place during the daytime, and during the wet season. But the team also discovered a few remarkable exceptions.

It is long known that aerosols, directly and indirectly, affect clouds and precipitation. But very few studies have focused on the opposite: the question of how clouds modify aerosol properties. Therefore, Luiz Machado and his colleagues looked into this process at ATTO. Specifically, they studied how weather events influenced the size distribution of aerosol particles.

The Amazon rain forest plays a major role in global hydrological cycling. Biogenic aerosols, such as pollen, fungi, and spores likely influence the formation of clouds and precipitation. However, there are many different types of bioaerosols. The particles vary considerably in size, morphology, mixing state, as well as behavior like hygroscopicity (how much particles attract water) and metabolic activity. Therefore, it is likely that not only the amount of bioaerosols affects the hydrological cycle, but also the types of aerosols present.

Ramsay et al. measured inorganic trace gases such as ammonia and nitric acid and aerosols in the dry season at ATTO. They are to serve as baseline values for their concentration and fluxes in the atmosphere and are a first step in deciphering exchange processes of inorganic trace gases between the Amazon rainforest and the atmosphere.

Soot and other aerosols from biomass burning can influence regional and global weather and climate. Lixia Liu and her colleagues studied how this affects the Amazon Basin during the dry season. While there are many different interactions between biomass burning aerosols and climate, they found that they overall lead to fewer and weaker rain events in the Amazon rainforest.

When forests burn those fires produce a lot of smoke. And that smoke usually contains soot, also called “black carbon”. Black carbon particles are aerosols that absorb radiation and as such can warm the Earth’s atmosphere and climate. But we still have much to learn about aerosols, their properties, and distribution in the atmosphere. One of those things is the question of how black carbon emitted from biomass burning in Africa (i.e. forests, grasslands, savannas etc.) is transported across the Atlantic and into the Amazon basin, and what role it plays there. Bruna Holanda and her co-authors tackled this in their new study published in ACP.

In a new study, Dr. Haijie Tong and co-authors studied a subset of PM2.5, the so-called highly oxygenated molecules (HOMs) and its relationship with radical yield and aerosol oxidative potential. They analyzed fine particulate matter in the air in multiple locations. This including the highly polluted megacity Bejing and in the pristine rainforest at ATTO. They wanted to get insights into the chemical characteristic and evolutions of these HOM particles. In particular, they wanted to find out more about the potential of HOMs to form free radicals. These are highly reactive species with unpaired electrons.